ISSN electrónico: 1885-5210

DOI:https://doi.org/10.14201/rmc20211712532

USING FILMS TO TEACH PUBLIC HEALTH TO PORTUGUESE MEDICAL STUDENTS

Utilizar películas para enseñar Salud Pública a los estudiantes de medicina portugueses

Guilherme GONÇALVES; Carlos CARVALHO; Martha SACCO

Instituto de Ciencias Biomédicas Abel Salazar (ICBAS), Universidad do Oporto (UP), Oporto (Portugal).

Corresponding author: Guilherme Gonçalves.

E-mail address: aggoncalves@icbas.up.pt

Received 28 February de 2020; accepted 18 April 2020.

Summary

Few published articles addressed the use of films to teach public health. This article describes our experience using films to teach public health to medical students from 2014 to 2017. Students were randomly allocated to groups and specific movies. Each group had three weeks to show and discuss the film in the classroom. Six films were used. After the exam, students were asked to complete a questionnaire. A Likert scale (1 to 5) was used in each question. The course unit was part of the 5th year of the Masters in Medicine curriculum taught at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar. This study reports the answers given by 494 students (94.8%). More than 76% of the students graded the usefulness of the course unit with the highest values of the scale (4-5). That percentage was above 86% and 89% respectively for the items contents and methods. In general, students mentioned that they had learnt a lot on the subject, especially in the films And the Band Played On, Sicko and Super Size Me. Using films to teach public health to medical students appears to be an effective way of imparting the relevant public health knowledge.

Keywords: Public Health; medical; education; motion pictures.

Resumen

Pocos artículos abordan el uso de películas para enseñar salud pública. Este artículo describe nuestra experiencia utilizando películas para enseñar salud pública a los estudiantes de medicina desde 2014 a 2017. Los estudiantes fueron asignados al azar en grupos y películas específicas. Cada grupo tuvo tres semanas para mostrar y discutir la película en la clase. Se utilizaron seis películas. Después del examen, se pidió a los estudiantes que completaran un cuestionario. Se utilizó una escala Likert (1-5) en cada pregunta. La asignatura formaba parte del 5º año del plan de estudios de la Maestría en Medicina que fue impartida en el Instituto de Ciencias Biomédicas Abel Salazar. Este estudio reporta las respuestas de 494 estudiantes (94,8%). Más del 76% de los estudiantes calificaron la utilidad de la asignatura con los valores más altos de la escala (4-5). Ese porcentaje fue superior al 86% y 89% respectivamente para los ítems contenidos y métodos. En general, los estudiantes mencionaron que habían aprendido mucho, especialmente en las películas En el filo de la duda, Sicko y Súper engórdame. El uso de películas para enseñar salud pública a estudiantes de medicina parece ser una forma efectiva de impartir los conocimientos pertinentes de salud pública.

Palabras clave: Salud Pública; medicina; educación; películas.

Introduction

Cinema has been used in medical education for years. Specific experiences and opinions have been documented in various publications, including a very interesting review paper1. Besides the positive feedback of teachers and students involved in such teaching and learning approaches, there are some recognized conceptual bases to support the use of films in health care education1. Some published articles have focused on general methodological aspects1, whereas other publications tackled the use of movies in the teaching of a variety of academic / medical disciplines. Mental health2,3,4 seems to have been the predominant area but articles have also addressed the use of films to teach other areas / specialties, including clinical pharmacology5,6 and public health7,8,9. The only published article from Portugal that we identified used films to teach drug addiction to medical students10. There is also a book, written in Portuguese, on the use of films to teach family medicine11.

We identified three articles describing the use of films to teach Public Health (PH) as part of a medical degree. Gallagher et al7,8 from the University of Otago, New Zealand, published on the use of commercial movies to teach PH to medical students. They mentioned the chosen films and described the methods used, also reporting the students opinions collected through questionnaires. In 2018, Wade et al reported the results of a survey on the use of movies to teach PH9 answered by faculty members and undergraduate students, from the University of Washington. Consequent to that it was posted in that university’s site, the text «Can movies teach public health lessons?» that briefly summarizes the issues of using movies to teach PH. In both cases (New Zealand and the USA) the approaches seem to work well and show good potential to be developed.

The Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar, University of Porto (ICBAS-UP), Portugal, was founded in 1976. Besides Medicine, it has been offering graduations in Aquatic Sciences, Biochemistry and Veterinary Medicine. From 2007-2008 to 2013-2014, the ICBAS taught a course unit (CU) in PH, as part of the medical degree, based on the concept of Evidence-based Public Health12. The contents and methods were described and assessed using an anonymous questionnaire, answered by the students13. The student’s workload was also evaluated14. As part of that CU, one group presented a seminar on an alternative way to teach PH to undergraduate medical students, using movies. That presentation stimulated us to do some bibliographic search on the use of movies to teach PH, as a result of which we changed how we taught the CU to include movie-based teaching from 2014/15 to 2017/18.

This article describes our experience of using films to teach public health to medical students over a three-year period from 2014-2017.

Setting

The course unit (CU) named Saúde Pública (Public Health - PH) was part of the Masters in Medicine curriculum (MIM) of ICBAS. It was taught to medical students of the 5th year, over a 15 week period (2 hours per week with a total of 30 contact hours). The first two weeks (called Primer) covered the objectives of the CU and key PH topics in lectures. These topics overlapped with the themes of the chosen films. Subsequently, students were divided into groups, with each group being allocated one film. The five films were: And the Band Played On (1993) by Roger Spottiswoode, Super Size Me (2004) by Morgan Spurlock, Thank You for Smoking (2005) by Kim Dickens, The Constant Gardener (2005) by Fernando Meirelles and Sicko (2007) by Michael Moore. In 2016-2017, Super Size Me was replaced by the film Fed Up (2014) by Stephanie Soechtig.

In the first two weeks (Primer), the faculty members explained the objectives of the study unit and its functioning. A film was seen in the classroom and the teacher lead the discussion on the most relevant PH features addressed. Students were encouraged to give their opinions and raise questions. This intended to be illustrative of the approach expected from the groups in the remaining CU.

Students were randomly allocated to the groups and in the third week the faculty members had meetings with all groups to discuss the movies and assist them in the preparation of the presentations and discussions in the classes. There were written guidelines with the objectives and methods used in the CU, but there was a space for students creativity and alternative strategies.

In the remaining CU each group had three weeks to show and discuss the film in the classroom. Students of the group were supposed to initially present the movie to their colleagues and comment on it in the end. A discussion with all students (besides those of the film group) was highly encouraged. Lecturers only intervened if there was any wrong concept or information being conveyed. The entire movie was supposed to be seen in the classes but the student’s group in charge was free to cut some parts if considered not relevant to the discussion. In the end, students not belonging to the group in charge filled a two page questionnaire, produced by their colleagues. The results were used in the report that each group had to write on the movie and its discussion in the classes.

At the end of the PH course unit, there was a final written exam with questions about the movies and given texts directly related to them or to the PH problem addressed.

Questionnaire

After the exam, students were asked to complete a questionnaire. A Likert scale (from 1=bad to 5=excellent, or equivalent values related to the specific question) was used in each question. General questions addressed usefulness, contents and teaching method used in this CU. The same questions were asked for each of the six movies: usefulness for public health; how much they had learned; whether they intended to change their behavior on health aspects addressed in the movie; potential usefulness of the movie to be used in health education activities directed to the general population.

Results

In the three academic years considered, 521 students attended the final exam. The majority (95.4% = 497) answered the questionnaire, but three questionnaires were so incomplete that they were rejected from analysis. Thus, this study reports the answers given in 494 questionnaires (94.8% of students). Nevertheless, some questions were not answered in all questionnaires and thus not all questions have a total of 494 valid answers.

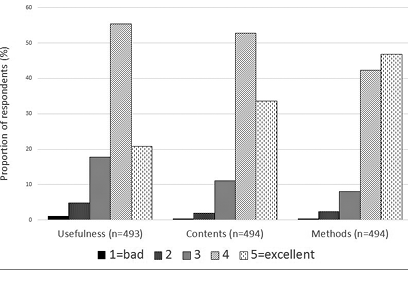

More than 76% of the students graded the usefulness of the CU with the highest values (4 or 5) of the Likert scale (Figure 1). That percentage was above 86% and 89% respectively for the items contents and methods (the use of movies to learn PH). It can be seen in the Figure that there was an increasing trend, from usefulness to methods, in the percentage of students assigning the value 5 (excellent).

Most films used in the study unit had never been seen by the students. The Constant Gardener, had been seen by 38.4% of the students as a recreational activity while the film Super Size Me was the one which had been seen in a teaching setting by more students (14.5%). Unfortunately it was not asked whether that had happen in the medical course or other learning context.

The answers on specific films are summarized in the Table 1. All films were considered to be very useful for this course unit (public health). The majority of students assigned values 4-5 of the Likert scale to all movies. The least considered film was The Constant Gardener while the highest values were allocated to Sicko.

On the question «How much did you learn on the subject?» more than 75% of the students rated 4-5 in three films (And the Band Played On, Sicko and Super Size Me), while for the films The Constant Gardener and Thank you for smoking, more students rated 2-3 than the values 4-5.

Figure 1. Students opinions on the usefulness, contents and methods of the course unit (Public Health).

When considering the question «Do you intend to change your behavior on some health aspects addressed in the film?» very few students expressed an intention to make behavioral changes in their lives, considering the health aspects addressed in four of the films (Table 1). Many considered that they would make «no changes at all». A different pattern was observed when answering about the two movies related with food and eating habits Super Size Me and Fed Up: respectively 43% and 51% of students intended to make big changes (values 4 and 5 in the Likert scale).When expressing their opinion on the «Potential usefulness of the film to be used in health education (general population)» Students con- sidered the films differently, from the very useful Fed Up to the least useful The Constant Gardener.

Discussion

The authors of this article got the general idea that the method works well. The participation in the discussions was good and the main points, relevant for each PH problem, were addressed. Moreover it was clear for us that the alternative of using traditional lecture-based approaches would not have transmitted the same quantity of relevant information, let alone motivate the students for the importance of the PH problems addressed in the movies. But of course this is a subjective opinion which makes no proof in terms of an evidence based decision on using movies to teach PH to undergraduate students. Nevertheless, in the Public Health CU, even before the use of films, students had clearly rated classical lecture-based approaches as being much less effective than alternative pedagogic methods actively engaging students, when learning objectives were assessed13.

Due to the novelty and importance of the articles published by Gallagher et al7,8 some comparisons with the present study might be relevant. Unlike those authors, we chose to show the entire movies within the teaching sessions which seems to be a minority option among those using this teaching approach1. We wanted to be sure that all students actually watched the (same) movies. On the other hand we wanted to get a better insight of the approach since we were using it by the first time ourselves. The only problem is that it may limit the comparability of our study with those published by Gallagher. Three movies are common in our study and the one from New Zealand. In the case of And the Band Played On and The Constant Gardener, the proportions of students who had previously seen the two films before the PH course unit was similar in Portugal and New Zealand, but less Portuguese students (9.0%) than those from New Zealand (37.0%) had seen the film Sicko before7. Our results shown in the Table are difficult to compare with those from Gallagher et al8 because questions were not precisely the same and, unlike the study from New Zealand, in our study all questions used a 5 point Likert scale. Nevertheless, reading the main findings of Gallagher in the discussion section it seems obvious that in the end, medical students from both countries considered that the use of films in their public health training was a very positive approach. Furthermore we found the Gallagher’s «Tips for using movies effectively»8 very useful and followed most of them. We got the impression that they work well.

Table 1. Students opinion on the five films used in the course unit.

|

Question |

And the Band Played On |

Sicko |

The Constant Gardner |

Thank you for smoking |

Super Size Me |

Fed U |

|

Usefulness of the film to this course unit |

n=481 |

n=484 |

n=459 |

n=485 |

n=339 |

n=142 |

|

4 (00.8%) |

3 (00.6%) |

10 (02.0%) |

6 (01.2%) |

3 (00.9%) |

1 (00.7 %) |

|

|

4 (00.8%) |

3 (00.6%) |

14 (02.8%) |

14 (02.9%) |

3 (00.9%) |

1 (00.7 %) |

|

|

34 (07.1%) |

30 (06.2%) |

82 (16.6%) |

66 (13.6%) |

21 (06.2%) |

13 (09.2%) |

|

|

141 (29.3%) |

138 (28.5%) |

183 (39.9%) |

167 (34.4%) |

102 (30.1%) |

39 (27.5%) |

|

|

258 (62.0%) |

310 (64.0%) |

170 (37.0%) |

232 (47.8%) |

210 (61.9%) |

82 (62.0%) |

|

|

How much did you learn on the subject? |

n=483 |

n=486 |

n=458 |

n=487 |

n=341 |

n=142 |

|

3 (00.6%) |

2 (00.4%) |

20 (04.4%) |

29 (06.0%) |

3 (00.9%) |

0 (00.0 %) |

|

|

23 (04.8%) |

17 (03.5%) |

67 (14.6%) |

68 (14.0%) |

20 (05.9%) |

9 (06.3%) |

|

|

87 (18.0%) |

72 (14.8%) |

177 (38.7%) |

184 (38.7%) |

50 (17.7%) |

43 (30.3%) |

|

|

226 (46.8%) |

174 (35.8%) |

148 (32.3%) |

160 (32.9%) |

166 (48.7%) |

55 (38.7%) |

|

|

144 (29.8%) |

221 (45.5%) |

46 (10.0%) |

46 (09.4%) |

102 (29.9%) |

35 (24.6%) |

|

|

Do you intend to change your behav iour on some health aspects addressed in the film? |

n=466 |

n=470 |

n=441 |

n=475 |

n=339 |

n=139 |

|

149 (32.0%) |

140 (29.8%) |

147 (33.3%) |

180 (37.9%) |

72 (21.3%) |

9 (06.5%) |

|

|

87 (18.7%) |

74 (15.7%) |

74 (16.8%) |

76 (16.0%) |

46 (13.6%) |

14 (10.1%) |

|

|

132 (28.3%) |

132 (281%) |

128 (29.0%) |

111 (23.4%) |

74 (21.8%) |

45 (32.4%) |

|

|

66 (14.2%) |

86 (18.3%) |

66 (15.0%) |

63 (13.3%) |

94 (27.7%) |

39 (28.1%) |

|

|

32 (06.9%) |

38 (08.1%) |

26 (05.9%) |

45 (09.5%) |

53 (15.6%) |

32 (23.0%) |

|

|

Potential usefulness of the film to be used in health education (general population) |

n=479 |

n=481 |

n=451 |

n=484 |

n=338 |

n=142 |

|

28 (05.8%) |

25 (05.2%) |

41 (09.1%) |

18 (03.7%) |

25 (07.4%) |

0 (00.0%) |

|

|

58 (12.1%) |

45 (09.4%) |

67 (14.9%) |

23 (04.8%) |

35 (10.4%) |

2 (01.4%) |

|

|

127 (22.5%) |

92 (19.1%) |

146 (32.4%) |

78 (24.6%) |

95 (28.1%) |

13 (09.2%) |

|

|

109 (22.8%) |

131 (27.2%) |

101 (22.4%) |

139 (28.7%) |

75 (22.2%) |

33 (23.2%) |

|

|

157 (32.8%) |

188 (39.1%) |

96 (21.3%) |

226 (46.7%) |

108 (32.0%) |

94 (66.2%) |

N=number of responders. Scores (1 to 5) of the Likert scale.

a. Not useful at all = 1 234Very useful = 5. b. I have learned almost nothing = 1 234I have learned a lot = 5. c. No changes at all = 1 234I intend to make big changes = 5. d. Not at all useful = 1 234Very useful = 5.

An interesting result from our study, which we had not read in previously published papers, was that films seem to have influenced the student’s intention to change their own health behaviors. A deep detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this study but, if the transtheoretical model15 is correct, the film Fed Up, was the more effective one leading Portuguese medical students to reach the «preparation stage» of health behavior and the one that they considered to have a best usefulness for use in health education directed to the general population. It is very curious that in all six movies, medical students ranked the potential for use in health education directed to the general population better than the effect on their own intention to change health behavior. Health promoting activities in university settings, with changes in the curricula and in the behaviors of the academic community members have been proposed within the context of national and international networks16. Our modest experience can just be seen has an example of an activity that can be integrated in the context of much wider interventions of that type.

It is also difficult to make valid comparisons with the findings reported in an article on the use of movies to teach PH, published in 2018 by Christopher Wade et al9, because questions were not precisely the same and Likert scales range were slightly different. Nevertheless like students and faculty members of that American university, we perceived the use of movies to teach PH as useful.

Conclusions

Using films to teach public health to medical students appears to be an effective way of imparting the relevant public health knowledge.

We decided to publish this experience and the results of the questionnaire because there were very few accounts on the use of films to teach PH. We believe that the consistency of the findings in such different countries would be important to infer causality17 when supporting decisions to use this teaching method. We would encourage colleagues from other settings to use films to teach public health and report on the details of their approaches.

Formally there is no epilogue section to be written but we fear an undesired end. Some faculty members of our school have seen our approach with some skepticism. Meanwhile, the curricular structure of our Master in Medicine was radically changed since the academic year of 2018-2019. The described course unit «public health» in the 5th year of the course was extinguished. There are two new study units related to public health but, in the whole medical course beginning in 2018-2019, study units related to the areas of community health, public health and epidemiology were reduced to 25% of the weight they had in the previous curriculum. Might this article be a contribution to the discussion of these issues. We do not believe that emphasizing the teaching of technological aspects of modern medicine at the expense of public health might be a good strategy in the curricular transformation of medical courses.

References

1. Darbyshire D, Baker P. A systematic review and thematic analysis of cinema in medical education. Med Humanit 2012; 38(1): 28-33.

2. Fitz GK, Poe RO. The role of a cinema seminar in psychiatric education. Am J Psychiat 1979; 136(2): 207-10.

3. Graf H, Abler B, Weydt P, Kamer T, Plener P. Development, Implementation, and Evaluation of a Movie-Based Curriculum to Teach Psychopathology. Teach Learn Med. 2014; 26(1): 86-9.

4. Wilson N, Heath D, Heath P, Gallagher P, Huthwaite M. Madness at the movies: prioritised movies for self-directed learning by medical students. Australas Psychiatry .2014; 22(5): 450-3.

5. Koren G. Awakenings: using a popular movie to teach clinical pharmacology. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1993; 53(1): 3-5.

6. Farre M, Bosch F, Roset PN, Baños JE. Putting clinical pharmacology in context: the use of popular movies. J Clin Pharmacology 2004; 44(1): 30-6.

7. Gallagher P, Wilson N, Edwards R, Cowie R, Baker MG. A pilot study of medical student attitudes to, and use of, commercial movies that address public health issues. BMC Res Notes 2011; 4: 111.

8. Gallagher P, Wilson N, Jane R. The efficient use of movies in a crowded curriculum. Clin Teach. 11 (2), 88-93.

9. Wade CH, Barrientos T, Macarulay M, Alderson W, Shibale PC, Le C. Student and Faculty Perspectives on the Use of Movies in Public Health Pedagogy. Pedagogy in Health Promotion 2017; 4(2): 131-9.

10. Pais de Lacerda A. Medical education: addiction and the cinema (drugs and gambling as a search for happiness) J Med Movies. 2005;1(4):95-102.

11. Blasco PG. Humanizando a Medicina. Uma metodologia com o cinema. São Paulo. Brazil: Centro Universitário São Camilo, 2011.

12. Brownson RC, Baker EA, Leet TL, Gillespie KN. Evidence-Based Public Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003.

13. Gonçalves G. Ensino da saúde pública baseada na evidência a estudantes de medicina portugueses. Acta Med Port 2011; 24(S2): 467-78.

14. Gonçalves G. Studying public health. Results from a questionnaire to estimate medical students’ workload. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2014; 116(2014): 2915-19.

15. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages of change in the modification of health behaviours Prog Behav Modif.1992; 28: 183-218.

16. Dooris M, Farrier A, Doherty S, Holt M, Monk R, Powell S. The UK Healthy Universities Self-Review Tool: Whole System Impact. Health Promot Int. 2018. 33(3): 448-57.

17. Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston / Toronto: Little, Brown and Company; 1987.

|

|

Guilherme Gonçalves. Médico de Salud Pública. Profesor asociado de Salud Comunitaria en la Universidad de Oporto (Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar - ICBAS), Portugal. |

|

|

Carlos Carvalho. Médico de Salud Pública. Profesor lector en la Universidad de Porto (ICBAS), Portugal. |

|

|

Martha Sacco. Médica pediatra licenciada por la Univesidad de São Paulo, Brasil. Investigadora visitante en la Universidad de Porto (ICBAS), Portugal. |